Hermeneutics is the theology of understanding divine communication. It asks how finite people, aided by the Holy Spirit, rightly understand the Scriptures that God inspired. The term comes from the Greek hermeneuein, to interpret or to make clear. In Christian usage, hermeneutics gives the principles and posture for faithful interpretation, while exegesis is the applied method that draws out a passage’s meaning within that framework. Exegesis operates under hermeneutics; it is the servant, not the master.

Evangelical hermeneutics rests on two complementary convictions. First, God breathed out the biblical text through human authors who wrote to real audiences in concrete settings. Second, the same Spirit who inspired the Word illumines readers to understand it rightly. Biblical study is theological research that aims to discover the meaning and significance of the text as God intended through the human author, not to invent new meanings for modern tastes (Smith, How to Do an Exegetical Study).

1. The Meaning and Purpose of Hermeneutics

Hermeneutics bridges the historical world of the text and the present world of the reader. It honors God’s revelation in language, literature, and history, and it welcomes the Spirit’s illumination so that understanding leads to obedience. The goal is not clever novelty but faithfulness: to hear what God said, to grasp what God means, and to live what God commands.

2. Historical Development of Biblical Hermeneutics

From Ezra to the Early Church

Interpretation is as old as Scripture itself. Nehemiah 8:8 records that the Levites read from the Law, explained it, and gave the sense so that the hearers understood. The early church continued this task with pastoral purpose. Augustine insisted that interpretation must accord with love of God and neighbor, since Scripture aims at charity rather than speculation.

The Reformation and the Return to Context

The Reformers recovered the grammatical historical approach. Luther taught that Scripture interprets Scripture. Calvin said that an interpreter’s duty is to bring out the author’s meaning rather than thrust in one’s own. The focus moved from free allegory to the plain sense that the Spirit inspired through human authors to real congregations.

Modern Conversations and Evangelical Renewal

Modern theory contributed helpful questions about language, history, and understanding. Yet evangelicals maintained that the Bible is not merely a human word about God but God’s Word to humanity. Norman Geisler observed that sound interpretation refuses to reduce Scripture to an errant human witness and instead treats it as divinely trustworthy and authoritative (Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics).

3. Core Concepts of Hermeneutics

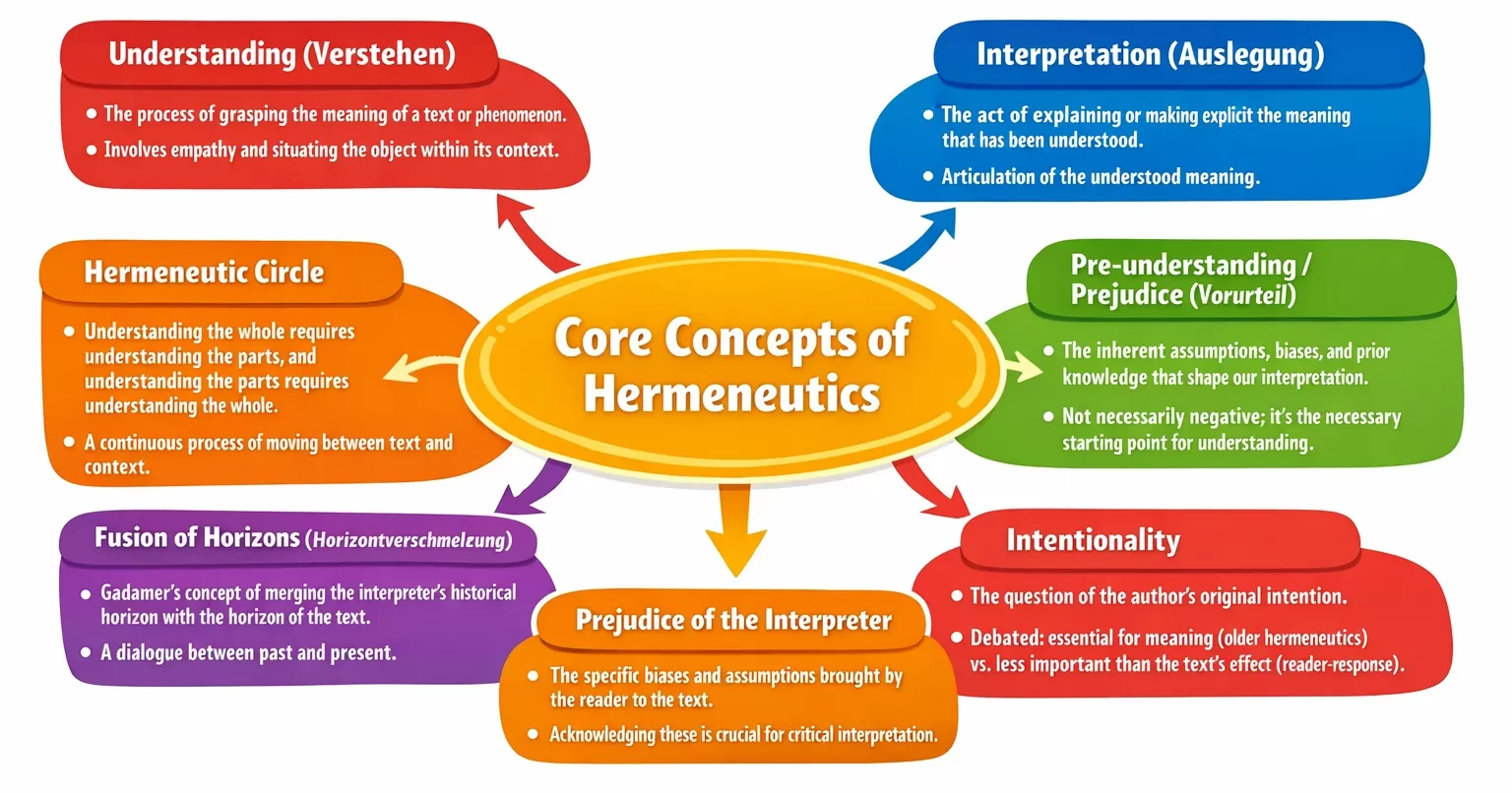

Understanding (Verstehen)

Understanding is the act of grasping a text’s meaning within its world. It calls for empathy, imagination, and attention to context. Jesus explained parables to His disciples in private, which shows that understanding often develops through patient listening and clarifying dialogue (Mark 4:10 to 12, 33 to 34). When you read a lament psalm, you step into a singer’s midnight and listen for the theology of hope that rises by dawn. Ask, What would an attentive first hearer have taken this to mean, and why would it matter for faith and life?

Interpretation (Auslegung)

Interpretation is the articulation of what has been understood. Philip asks the Ethiopian, Do you understand what you are reading, and then proceeds to explain Isaiah 53 in light of Christ (Acts 8:30 to 35). Interpretation connects the dots. It moves from comprehension to coherent explanation, from what the text meant then to how that same meaning speaks now. In preaching terms, it is where your study meets your people in clear, faithful words.

The Hermeneutic Circle

The hermeneutic circle describes how the parts and the whole inform one another. You read Romans 8 with the whole letter in view, and you read the whole letter with Romans 8 in view. Luke 24 provides a beautiful example. Jesus opens the Scriptures so that the disciples see Moses and the Prophets as a unified witness that the Christ must suffer and rise (Luke 24:25 to 27, 44 to 47). You move back and forth, text to canon and canon to text, until the sense coheres.

Pre understanding and Prejudice (Vorurteil)

Every reader brings assumptions to the Bible. Some are helpful; many need correction. Peter’s preconception about Gentiles was not abolished by better study habits but by a sheet let down from heaven and the Spirit’s rebuke, which then sent him back to the Scriptures with new eyes (Acts 10 to 11). Name your assumptions before the text names them for you. Pray, search, and allow Scripture to judge your traditions rather than using your traditions to judge Scripture. Gentle humor helps here. If you always find your favorite political point in every passage, you might be doing more mirror work than window work.

Fusion of Horizons (Horizontverschmelzung)

Hans-Georg Gadamer described understanding as the fusion of the text’s horizon with the reader’s horizon. Evangelicals receive this as a Spirit guided dialogue where timeless truth meets timely lives. The Sermon on the Mount did not expire in first century Galilee. Its horizon meets ours as the Spirit presses Jesus’s kingdom ethic into our daily choices, our speech patterns, and even our online comments. The horizon of the text remains authoritative, and our horizon is humbly transformed.

Intentionality

Where does meaning live in the author, text, or reader Evangelical conviction anchors meaning in divinely guided authorial intent, expressed in the text, and received by the church. Paul did not write Romans in code for future culture wars. He wrote a Spirit given pastoral letter to unite Jew and Gentile in the gospel. Respecting intentionality guards against using Scripture as a prop for preferences. It also guards against despair, because God actually meant to be understood.

Prejudice of the Interpreter

The interpreter’s biases are not merely theoretical. They show up in what we highlight, what we skip, and how fast we run to application. James warns teachers about stricter judgment (James 3:1), which includes our handling of the Word. Build a habit of inviting correction. Read across the canon, across the centuries, and across cultures in the global church. You will not lose your convictions by listening well. You will refine them.

4. Core Principles of Hermeneutics

Authorial Intent

Seek what the author meant before deciding what the text means to you. Every passage was written by a real person to real people for a real purpose. When Paul told Timothy to bring the cloak, he was not giving a secret code for modern believers to start a clothing drive. He was simply cold (2 Timothy 4:13). Yet the note reveals diligence and humanity that still instruct us. Following intent keeps us from using Scripture as a mirror for our opinions rather than a window to God’s truth. Calvin captured it well. The task is to bring out the meaning of the author, not to thrust our own in.

Contextual Reading

Context is the oxygen of interpretation. A verse without context can prove almost anything. Satan quoted Scripture to Jesus, and Jesus answered with Scripture in context, which shows the guardrail function of context for faithful reading (Matthew 4:1 to 11). Consider genre and setting. Read a psalm as poetry. Read a proverb as wise observation, not a mechanistic promise. Read a parable as a story that makes one or two piercing points rather than as a treasure map with one clue in every noun.

The Unity of Scripture

The canon speaks with a coherent voice about creation, fall, redemption, and restoration. Jesus said that the Scriptures bear witness about Him (John 5:39). The bronze serpent in Numbers 21 foreshadows the Son lifted up for life in John 3:14 to 15. Seeing the unity keeps us from chopping the Bible into unrelated moral bits. Leviticus and Luke are not strangers; they are kin who reveal the Holy One who saves sinners.

The Clarity of Scripture

God speaks to be understood. Psalm 19:7 says that His testimony makes wise the simple. Peter admits that some of Paul is hard to understand, but that is not the same as impossible to understand (2 Peter 3:16). The essentials for salvation and godliness are plain to believers who approach with faith and humility. Often the problem is not that the Bible is unclear, but that we do not like its clear claims.

Spiritual Illumination

The Spirit who inspired the Word illumines our minds to receive its meaning. The natural person does not accept the things of the Spirit of God, since they are spiritually discerned (1 Corinthians 2:12 to 14). Illumination is not a shortcut around study, and it is not a license for private meanings. It is God’s gracious work that turns reading into communion and study into worship. A simple prayer will often be your best hermeneutical tool. Lord, show me what You meant, and lead me to live it.

5. Interpretive Methods

Grammatical Historical

Attend to words, syntax, setting, and occasion. What did this mean for the original audience, and how does that same meaning carry forward? The Oxford Bible Commentary notes that we read Scripture as literature in history and as revelation in faith. Genre awareness belongs here. Narrative is not a command; a command in context may have a principle that still binds.

Canonical and Theological

Let Scripture interpret Scripture. Track themes across the canon. Ask how this text contributes to the Bible’s unified testimony to Christ. Practice biblical theology so that exegesis serves the whole counsel of God rather than isolated proof texts.

Practical Hermeneutics

Bring it together in ordinary study. With a parable, look for the main point Jesus drives home. With an epistle, follow the author’s flow of thought and the pastoral problem addressed. With a psalm, watch for parallelism, images, and the movement from complaint to trust. Test your sermon idea against the paragraph, the chapter, the book, and the canon.

6. Applying Hermeneutics in Bible Study and Ministry

- Pray first. Ask for illumination, wisdom, and obedience.

- Observe carefully. Note repeated words, connectors, and contrasts.

- Interpret responsibly. Seek authorial intent within context and genre.

- Correlate canonically. Compare Scripture with Scripture.

- Apply pastorally. Aim for transformation that fits the text’s purpose.

In my Smart Discipleship Model, I emphasize that the goal of biblical study is transformation rather than mere information. The aim is not data but discipleship, since understanding Scripture should always lead to faith in action.

7. The Sacred Task of Understanding

Hermeneutics unites heart, mind, and Spirit under God’s Word. As Boyce put it, revelation does not destroy the natural, but sanctifies it (Abstract of Systematic Theology). We do not master the text; the living Word masters us. Or, to borrow a pastoral smile, we are not trying to make the Bible say what we wish. We are learning to wish what the Bible says.

References

- Boyce, J. P. Abstract of Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: CCEL edition.

- Geisler, N. L. Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker.

- Oxford Bible Commentary. Ed. John Barton and John Muddiman. Oxford: OUP.

- Smith, K. G. How to Do an Exegetical Study. Guidance on author intended meaning and theological research posture.

- Vine, W. E., Unger, M. F., and White, W. Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary. Helpful on word meanings in context.