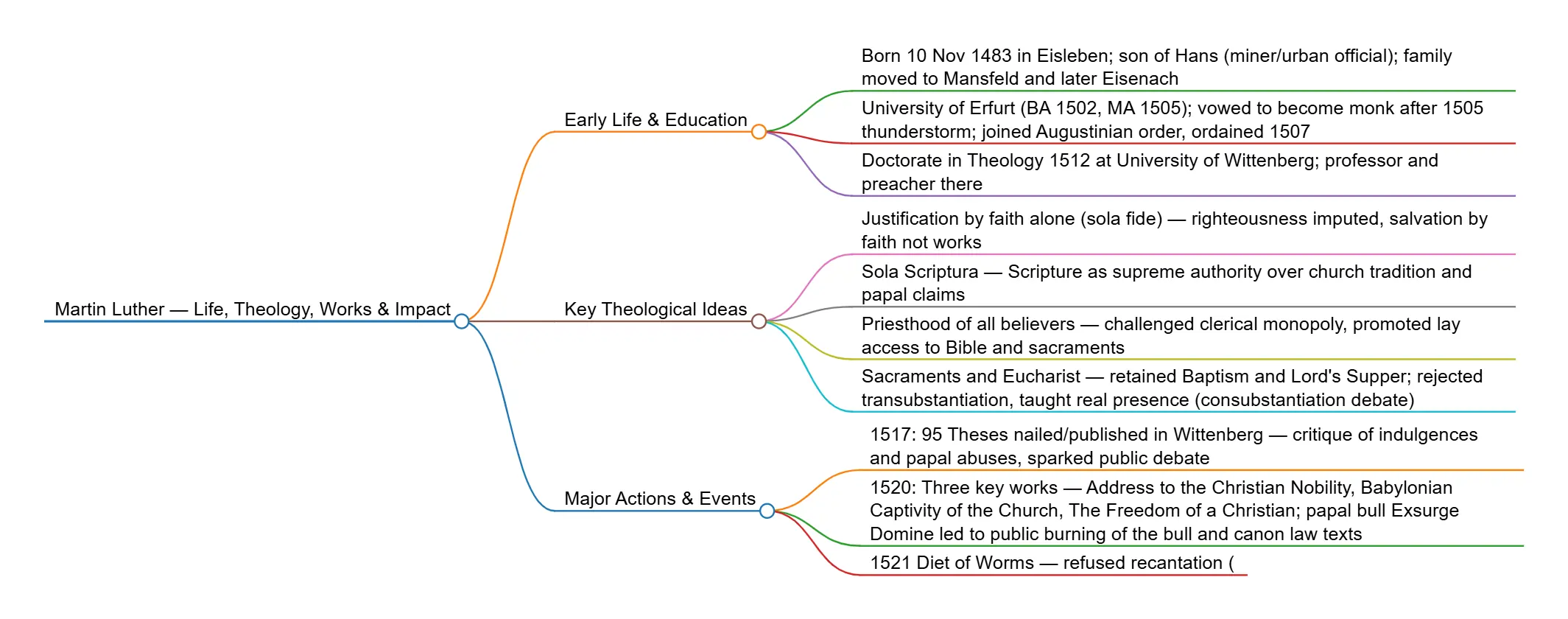

- Martin Luther Biography: Early Life and Education

- Academic Career and Rising Convictions

- The 95 Theses and the Spark of Reformation

- The Diet of Worms and the Question of Authority

- Return to Wittenberg, Marriage, and Pastoral Leadership

- Core Doctrines of Martin Luther Theology

- Major Works and Their Ongoing Importance

- Wider Impact on Church and Society

- Criticisms and Controversies

- Martin Luther Legacy

By Michael Mooney, Exec. Elder

This Martin Luther biography explains the life, theology, writings, and lasting significance of a reformer whose influence reaches across centuries. Martin Luther, born in 1483 and deceased in 1546 (at the age of 63), was a monk, professor, Bible translator, and church reformer whose work catalyzed the Protestant Reformation. He challenged indulgences and questioned papal authority, He insisted on justification by faith alone, and defended the principle of sola scriptura, (meaning Scripture as the final authority for faith and practice). By linking the message of grace to the life of congregations through preaching, catechisms, and hymns, Luther changed how ordinary Christians engaged the Bible and worship. The themes of this article align with search intent around Martin Luther theology, the 95 Theses, Protestant Reformation history, German Bible translation, and Martin Luther legacy, and they are presented with careful historical sourcing and clear language for a broad audience of ministers, and students alike (Hendrix, 2015).

Martin Luther Biography: Early Life and Education #

Martin Luther was born on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben in Saxony into a family that had risen from peasant status into modest prosperity through mining. His father, Hans Luther, invested in his son’s education with the aim that he would become a lawyer. Luther entered the University of Erfurt, where he earned a Master of Arts in 1505. He was regarded as an excellent student in the humanist curriculum, which emphasized grammar, rhetoric, logic, history, poetry, philosophy, and the classical languages of Latin and Greek. During the summer of 1505, a violent thunderstorm near Stotternheim left him terrified for his life. In fear, he vowed to Saint Anne that he would become a monk if he survived. He kept that vow and entered the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt, a move that surprised and disappointed his father but placed him on the path that would lead to the 95 Theses that altered Protestant Reformation history (Brecht, 1993; Hendrix, 2015).

The early monastic years showed Luther to be conscientious and intense. He fasted, prayed, and confessed with an eagerness to please God and quiet his conscience. Yet he remained deeply troubled, convinced that he could not do enough to stand before a holy God. The mentor who helped him most was Johann von Staupitz, the Vicar of the German Observant Augustinians, who directed Luther to the study of Scripture and the mercy of Christ. Through lecture preparation and close reading of the Psalms and the letters of Paul, Luther came to see righteousness in Romans 1:17 as a gift of God received by faith. That conviction centered his future teaching on justification by faith alone and formed the core of what would later be known as Martin Luther theology within the mainstream of Protestant Reformation theology (McGrath, 1985; Althaus, 1966).

Academic Career and Rising Convictions #

Ordained in 1507, Luther continued advanced study and in 1512 earned the Doctor of Theology. He joined the faculty of the University of Wittenberg, where he lectured on Psalms, Romans, Galatians, and Hebrews. His method of teaching combined rigorous exegesis with pastoral application. He did not reject the learning of the medieval schools lightly, but his growing conviction was that Scripture must interpret Scripture and that the grace of God in Christ stands at the heart of the biblical message. In this period Luther sharpened his contrast between human works and divine grace, and between human traditions and the authority of the biblical text. These themes would soon surface in public controversy, helping to define the Martin Luther legacy as a scholar who addressed ordinary people through preaching and through a clear standard German in sermons and catechisms (Hendrix, 2015; Kolb, 2005).

The 95 Theses and the Spark of Reformation #

On October 31, 1517, Luther published the document now famous as the Ninety Five Theses, formally titled Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences. The theses questioned abuses in the sale of indulgences and challenged the idea that papal pardons could remove guilt or the full penalty of sin. He urged that true repentance and trust in Christ, not financial transactions, are the path of forgiveness. Although he expected an academic debate, the printing press allowed his work to circulate quickly, and the 95 Theses became a focal point for wider discontent with church finance and discipline, fueling a movement that shaped Protestant Reformation history far beyond Wittenberg. The document remains a hinge text in Martin Luther theology because it links a pastoral concern for forgiveness with a principled appeal to Scripture as the final authority in doctrine and church practice (Luther, 1517/2003; Brecht, 1993).

The Diet of Worms and the Question of Authority #

In 1521, the Diet of Worms was held in the city of Worms, Germany as a formal assembly of the Holy Roman Empire. As the religious dispute deepened, Martin Luther was called to stand before this council in the presence of Emperor Charles V to address his teachings. There he was asked to recant the writings in which he attacked indulgences and defended his teaching on grace and the authority of Scripture. Luther answered that his conscience was captive to the Word of God and that he could not recant unless shown from Scripture that he was wrong. Some traditional accounts paraphrase his defense with the famous words that he stood and could do no other, though historians note that exact phrasing is uncertain. Regardless of phrasing, his position was consistent with sola scriptura. He was declared an outlaw, yet he found protection through the intervention of Prince Frederick the Wise. Hidden at Wartburg Castle, he began a German Bible translation that would democratize Scripture and shape the modern German language, a major pillar of the Martin Luther legacy known well beyond the boundaries of church history (Brecht, 1993; Hendrix, 2015).

Return to Wittenberg, Marriage, and Pastoral Leadership #

Luther returned to Wittenberg in 1522 to moderate reforms that were unfolding too rapidly and sometimes disorderly in his absence. He preached a series of sermons that combined firmness about the need for change with patience for people who needed time to learn the Gospel and its implications. In 1525 he married Katharina von Bora, a former Cistercian nun who had escaped the convent. Their home modeled Christian family life and hospitality, and their marriage produced six children. Luther wrote pastoral advice on marriage and vocation and insisted that all legitimate work could be a calling from God. His household became a dynamic center of teaching, hospitality, and practical piety. The domestic setting also offered Luther a platform to keep forming students and pastors through table talk, pastoral letters, and catechetical instruction, strengthening long term patterns of Protestant devotion and congregational life that remain part of Martin Luther theology in practice (Hendrix, 2015; Kolb, 2005).

Core Doctrines of Martin Luther Theology #

Justification by faith alone. Salvation is a gift of God received by trusting in Christ, not through human merit. Luther often called justification the article by which the church stands or falls, because it keeps Christ at the center and comforts troubled consciences with the promise of forgiveness in the Gospel. The classic text is Romans 3 to 5. Luther insisted that the message must be preached so that people hear and believe good news rather than a new set of rules to keep (Althaus, 1966; McGrath, 1985).

Scripture alone. Scripture is the final authority in matters of faith and practice. Tradition has a ministerial role, but only Scripture has a ruling voice. Luther’s reliance on the plain sense of Scripture was formed by his teaching work and his pastoral concern that God’s Word be accessible to common people in their own language. The principle of Scripture alone directed him to translate the Bible and to train families to use the Bible in daily prayer and instruction (McGrath, 1985; Kolb, 2005).

Priesthood of all believers. All baptized Christians share in a spiritual priesthood by which they have direct access to God through Christ, and all are called to serve neighbors in love. This did not abolish the pastoral office, but it placed clergy among the baptized rather than above them. It also elevated family life and ordinary work as arenas of service to God, giving dignity to vocations outside the church walls (Kolb, 2005; Hendrix, 2015).

The sacraments. Luther recognized Baptism and the Lord’s Supper as dominical sacraments instituted by Christ. He rejected the scholastic account of transubstantiation, yet he affirmed the real presence of Christ in the Supper through a sacramental union. He emphasized that sacraments deliver the promises of the Gospel and must be joined with the Word of God to benefit those who receive them in faith (Kolb, 2005).

Law and Gospel. Luther drew a careful distinction between the law and the Gospel. The law reveals God’s will, exposes sin, and curbs evil, but the Gospel is the promise of forgiveness and life through Christ. For preaching and pastoral care, the distinction protects the freedom of the Gospel and avoids turning Christianity into a new legal code (McGrath, 1985; Althaus, 1966).

Vocation and two kingdoms. Luther taught that God rules the world in two ways. Through the Gospel, God rules hearts by grace in the church. Through civil authority, God restrains evil and preserves order in society. This two kingdoms framework separates the saving work of Christ from civil power and offers a theology of citizenship, law, and responsibility that continues to shape discussions of church and state and belongs to the Martin Luther legacy in public life (Witte, 2002).

Major Works and Their Ongoing Importance #

The 95 Theses. This short but potent set of statements on indulgences addresses the nature of repentance, the limits of papal power, and the danger of trading money for spiritual benefit. Although concise, it framed the moral and theological concerns that would define Luther’s early public ministry and press the church to return to the Gospel of forgiveness through Christ alone. It remains central to any Martin Luther biography and to Protestant Reformation history (Luther, 1517/2003).

The Freedom of a Christian. Written in 1520, this treatise explains how the believer is free through faith yet bound in love to serve the neighbor. It shows how justification by faith creates a paradoxical freedom that expresses itself through active charity, a theme important for ethics and spirituality within the Martin Luther legacy (Hendrix, 2015).

The Bondage of the Will. Published in 1525 in response to Erasmus, this work argues that human will is bound by sin and that conversion is the work of God’s grace from beginning to end. Luther’s aim was to protect the Gospel from turning into a message of human achievement. The treatise remains an essential text for debates on grace, free will, and salvation in Protestant Reformation theology (Luther, 1525/1957).

The Small and Large Catechisms. Issued in 1529, these catechisms teach the Ten Commandments, the Apostles Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and the sacraments. The Small Catechism is written for families and is compact and memorable. The Large Catechism offers fuller explanation for pastors and teachers. Together they supplied a durable curriculum for Christian formation and still serve congregations today (Kolb, 2005).

German Bible translation. Between 1522 and 1534 Luther produced a complete German Bible. He aimed for a clear, common German that people could understand when they heard it read aloud. The translation encouraged personal and family Bible reading and shaped German literature and identity. The story of German Bible translation in the modern era begins with Luther’s work at Wartburg and Wittenberg and remains a cultural pillar of the Martin Luther legacy (Brecht, 1993; Hendrix, 2015).

Hymnody and worship reform. Luther wrote hymns and supported congregational singing. A Mighty Fortress Is Our God is the most famous example. By placing the Gospel into the mouths of worshipers through music, he created a pattern of participation that has remained a hallmark of Protestant worship. His contributions show that Martin Luther theology was never only academic. It was sung, prayed, and taught in homes and churches (Kolb, 2005).

Wider Impact on Church and Society #

Luther’s reform linked theology to social and cultural change. The alignment of preaching, catechesis, and song generated a new style of worship centered on the Word and the sacraments in the language of the people. The emphasis on Scripture and education helped create schools for boys and girls and promoted literacy throughout the German territories and beyond. Families were equipped to pray and teach with the Small Catechism at the dinner table. Printers prospered by producing Bibles, sermons, pamphlets, and hymns. These patterns formed the infrastructure of a learning church that encouraged private reading, public discussion, and civic responsibility. In the framework of two kingdoms, Luther taught that Christians should be good citizens, respect magistrates, and work for the common good, while remembering that salvation rests in Christ and not in political success. All of these elements are part of the Protestant Reformation impact as historians narrate it in European and global contexts, and they are part of the Martin Luther legacy that persists in today’s congregations and seminaries (Witte, 2002; Hendrix, 2015; McGrath, 1985).

Criticisms and Controversies #

A fair Martin Luther biography must also reckon with his failings and the controversies of his time. In the Peasants War of 1524 to 1525, Luther initially sympathized with certain grievances but opposed the violent uprising. In the pamphlet Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants, he urged rulers to restore order. Many later readers judge his rhetoric severe and his counsel too closely aligned with the interests of princes. The episode cooled support among some commoners and remains a disputed chapter in Protestant Reformation history (Brecht, 1993).

Luther’s later writings against Jewish people are another grave matter. In works such as On the Jews and Their Lies, he used harsh language and proposed policies that Christians today reject. Modern Lutheran bodies have repudiated (reject) these writings. A notable example is the 1994 Declaration to the Jewish Community by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, which rejects Luther’s anti Jewish polemics and affirms the dignity of Jewish neighbors. Any account of Martin Luther theology must acknowledge this moral failure and distinguish Luther’s best theological insights from the toxic rhetoric of his late polemics (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America [ELCA], 1994; Hendrix, 2015).

Luther also clashed with other reformers. The Marburg Colloquy of 1529 brought Luther and Ulrich Zwingli together in hopes of uniting the reform movements. They agreed on many points but could not reach unity on the presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper. Luther insisted on the real presence, while Zwingli emphasized memorial and spiritual presence. The failure to agree prevented an organized Protestant front, a reminder that reform in the sixteenth century was diverse and contentious. This dispute continues to inform discussions of sacramental theology among Protestants and belongs to the ongoing Protestant Reformation impact in ecclesiology (pertaining to the church) and worship (McGrath, 1985; Kolb, 2005).

Martin Luther Legacy #

The Martin Luther legacy rests on a combination of doctrinal clarity, pastoral sensitivity, and cultural creativity. He is a principal figure in Protestant Reformation history because he was able to connect the classroom with the pulpit and the family table. He linked justification by faith with the transformation of daily life in vocation and worship. He put the Bible in the language of the people and equipped parents, pastors, and school teachers to form children in the faith. Even his weaknesses are instructive because they show the need to read reformers with discernment, to keep Christ at the center, and to remember that the church is called to bear witness with humility and love.

Martin Luther’s theology remains relevant today through ongoing debates about grace and works, authority and tradition, and Christian freedom and responsibility. It also shapes the rhythms of congregational life, where Scripture and song embed the Gospel into the habits of the heart. In that sense, the most enduring part of his legacy is the call to return to the Word of God and to trust the promise of Christ above all else. This theme continues to guide many Christians around the world today. (Hendrix, 2015; Althaus, 1966).

References #

Althaus, P. (1966). The Theology of Martin Luther. Fortress Press.

Brecht, M. (1993). Martin Luther: His Road to Reformation 1483 to 1521. Fortress Press.

Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. (1994). Declaration to the Jewish Community. ELCA.

Hendrix, S. (2015). Martin Luther: Visionary Reformer. Yale University Press.

Kolb, R. (2005). Martin Luther: Confessor of the Faith. Oxford University Press.

Luther, M. (1517/2003). The 95 Theses and Other Writings. Penguin Classics.

Luther, M. (1525/1957). The Bondage of the Will (J. I. Packer and O. R. Johnston, Trans.). Revell.

McGrath, A. E. (1985). The Intellectual Origins of the European Reformation. Blackwell.

Witte, J. (2002). Law and Protestantism: The Legal Teachings of the Lutheran Reformation. Cambridge University Press.